Fonamentar el lideratge en el treball de progressar

Si el lideratge és diferent de la capacitat de guanyar-se una autoritat formal o informal i, per tant, és més que l'habilitat de guanyar-se "seguidors" "atreure influència i acumular poder", en què es pot basar la nostra concepció del lideratge?

El llenguatge ens falla en molts aspectes de la vida i ens atrapa en una sèrie d'assumpcions culturals com passa amb el bestiar tancat en una cleda. Els pronoms de gènere, per exemple, ens acorralen en ensenyar-nos de Déu és un ell, la qual cosa distancia cada vegada més les nenes i les dones de l'experiència de la divinitat en elles, i els homes de les virtuts tradicionalment femenines.

El llenguatge ens falla, també, quan tractem, analitzem i practiquem el lideratge. Usualment parlem de ¿líders¿ en les organitzacions o en la política quan realment ens referim a persones que ocupen llocs d'autoritat directiva o política. Si bé s¿ha confós el lideratge amb l'autoritat en gairebé tots els articles periodístics i acadèmics sobre ¿lideratge¿ que s¿han escrit els darrers cent anys, sabem intuïtivament que aquests dos fenòmens són diferents quan, en la política i en els negocis, sovint ens lamentem perquè ¿el líder no exerceix cap mena de lideratge.¿ Això és una contradicció terminològica, que es resol distingint el lideratge de l¿autoritat, ja que de fet el que volem dir és que ¿les persones que tenen l¿autoritat no estan exercint cap lideratge¿.El fet de si les persones amb autoritat formal, carismàtica o informal posen en pràctica efectivament el lideratge sobre qualsevol assumpte concret en un moment determinat és tota una altra qüestió, que s¿hauria de resoldre amb uns criteris diferents dels que s¿utilitzen per definir una relació de poders formals o d¿influència informal. Com sabem, hi ha moltíssimes persones capacitades per guanyar-se diferents tipus d'autoritat formal i informal i, per tant, per guanyar-se uns seguidors, però que no són líders.

A més, suposem que existeix una relació lògica entre les paraules líder i seguidor, com si aquest duo tingués una estructura absoluta i una lògica inherent. No és així. El lideratge més interessant és el que actua de manera que ningú no experimenta res remotament similar a una experiència de ¿seguiment¿. De fet, la majoria dels líders mobilitzen els qui opositors o els qui es miren a veure-les passar, a part dels aliats i els amics. Els aliats i els amics vénen molt fàcilment; són els opositors els qui tenen més a perdre en qualsevol procés important de canvi. Quan són mobilitzats, els aliats i els amics es converteixen no tan sols en seguidors, sinó en participants actius ¿treballadors o ciutadans, que sovint es converteixen en líders ells mateixos assumint la responsabilitat d'afrontar reptes difícils que estan al seu abast, a vegades més enllà de les expectatives i de la seva autoritat. Es converteixen en socis. I, quan són mobilitzats, els opositors i els qui s¿ho miren a veure-les passar s¿impliquen en els assumptes, se senten provocats a afrontar els problemes de pèrdua, lleialtat i competència que són implícits en el canvi que se'ls insta a realitzar. De fet, potser continuen lluitant, oferint una font constant de punts de vista diversos, necessaris per a l'èxit adaptatiu del negoci o de la comunitat. Lluny de convertir-se en ¿alineats¿ i lluny de qualsevol experiència de ¿seguiment¿, són mobilitzats pels líders a enfrontar-se a noves complexitats que requereixen concessions en les seves formes de treballar o de viure. Aquest és el treball de progressar. Evidentment, amb el temps poden començar a confiar, admirar i apreciar la persona o el grup que exerceixen el lideratge, i així conferir-los una certa autoritat informal, però en general no manifesten aquesta estima o confiança amb la frase: ¿M'he convertit en un seguidor.¿ Dubto que el governador d¿Alabama, George Wallace, després de la seva conversió a favor dels drets civils, es veiés a si mateix com un ¿seguidor¿ del Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. El més probable i apropiat és que Wallace es veiés com a adversari polític i com a col·lega de King en la lluita de la política populista americana. I encara que Bernard Lafayette estava entre els aliats naturals de King, dubto també que es veiés com a seguidor de King quan va recórrer els carrers de Selma a principi de 1965 amb una camisa tacada de sang per tal de mobilitzar la població negra de classe mitjana que arrisquessin la seguretat que s'havien guanyat amb la suor del seu front unint-se a les manifestacions en favor del dret a votar. Imagino que es tenia a si mateix per altre líder i col·laborador del moviment.

Si el lideratge és diferent de la capacitat de guanyar-se una autoritat formal o informal i, per tant, és més que l'habilitat de guanyar-se ¿seguidors¿ ¿atreure influència i acumular poder¿, en què es pot basar la nostra concepció del lideratge?

El lideratge es produeix en un context de problemes i desafiaments. De fet, té poc sentit descriure el lideratge quan tot i tots els integrants d'una organització funcionen bé, fins i tot quan els processos d'influència i autoritat abunden en la coordinació de l'activitat rutinària. A més, no és per qualsevol tipus de problema que el lideratge es necessita i es converteix en una pràctica rellevant. El lideratge és necessari per a les empreses i les comunitats quan les persones han d'afrontar reptes difícils, quan han de canviar les seves formes d'actuar per tal de prosperar, quan ja no n¿hi ha prou a continuar actuant segons les estructures, els procediments i els processos actuals. Són els anomenats reptes adaptatius. Més enllà dels problemes tècnics, per als quals n¿hi ha prou amb l'experiència autoritzada i directiva, els reptes adaptatius requereixen un lideratge que comprometi les persones a afrontar les noves realitats i a canviar les prioritats, les actituds i el comportament tant com sigui necessari per prosperar en un món canviant.

Mobilitzar les persones per respondre als reptes adaptatius és, doncs, el nucli de la pràctica del lideratge. A curt termini, el lideratge és una activitat que mobilitza les persones per satisfer un repte immediat. A mitjà i a llarg termini, el lideratge genera noves normes culturals que permeten a les persones donar resposta a un flux continu de reptes adaptatius en un món que probablement plantejarà de manera constant una sèrie de realitats i pressions. Així, molt a llarg termini, el lideratge desenvolupa la capacitat adaptativa, o adaptabilitat, d'una organització o comunitat.

L'objecte de l'adaptabilitat cultural i la pràctica del lideratge que genera és una gran línia divisòria. En aquest breu article, esmento vuit propietats del treball adaptatiu. El lideratge fonamentat en el creixement i el desenvolupament adaptatiu d'una organització o comunitat comença quan aquestes propietats es comprenen.

Primera, un repte adaptatiu és una distància entre les aspiracions i la realitat que requereix una resposta que està fora del repertori habitual. Mentre els problemes tècnics, en gran part, es poden remetre fàcilment a l'experiència actual, els reptes adaptatius no. Certament, tot problema es pot entendre com una distància entre les aspiracions i la realitat. El que distingeix els problemes tècnics dels reptes adaptatius és si aquesta distància es pot cobrir aplicant el know-how existent o no. Per exemple, un pacient va al metge perquè té una infecció, i el metge utilitza els seus coneixements per diagnosticar la malaltia i prescriure-hi un remei; es tracta d'un problema tècnic.

En canvi, un repte adaptatiu sorgeix quan la distància entre l¿estat desitjat i la realitat no es pot cobrir utilitzant només els plantejaments existents. Progressar en una situació requereix molt més que la mera aplicació de l'experiència actual, la presa de decisions autoritzada, els procediments estàndard d'actuació o els comportaments culturalment informats. Per exemple, un pacient amb una malaltia cardíaca probablement ha de canviar l¿estil de vida: la dieta, l'exercici, l'hàbit de fumar i els desequilibris que causen el gens saludable estrès. Per dur a terme aquests canvis, el pacient s¿ha de responsabilitzar de la seva salut i aprendre a adoptar unes noves prioritats i hàbits. Philip Selznick va descriure aquesta distinció entre reptes ¿rutinaris¿ i ¿crítics¿ en la seva monografia bàsica de 1957, Leadership in Administration.

Segona, els reptes adaptatius exigeixen un aprenentatge. Només hi ha un repte adaptatiu quan el progrés requereix, en certa manera, una readaptació de les pròpies formes de pensar i d'obrar de les persones. La distància entre les aspiracions i la realitat es redueix quan aprenem noves formes. Així, una firma de consultoria pot oferir una anàlisi de diagnòstic brillant i una sèrie de recomanacions, però no es resoldrà res fins que aquesta anàlisi i aquestes recomanacions es visquin de la forma nova en què actuïn les persones. Fins llavors, el que consultor ha ofert no són solucions, sinó propostes.

Tercera, amb els reptes adaptatius, les persones que tenen el problema són el problema i són la solució. Els reptes adaptatius requereixen un desplaçament de la responsabilitat, que passa de recaure sobre les persones que tenen l'autoritat i l'estructura de l'autoritat, a fer-lo sobre els propis stakeholders. Enfront de la resolució de problemes experta, el treball adaptatiu demana una forma diferent de deliberació i d'assumpció de responsabilitats. En fer el treball adaptatiu, cal que la responsabilitat es percebi de forma generalitzada. En el cas òptim, una organització manifestaria als seus membres que existeixen molts problemes tècnics, per a la resolució dels quals és adequat i eficient recórrer a l'autoritat, però també una sèrie de reptes adaptatius, per a la resolució dels quals resulta contraproduent recórrer a l'autoritat. Quan les persones incorren en l'error típic de tractar els reptes adaptatius com si fossin tècnics, esperen que la persona que posseeix l'autoritat sàpiga què cal fer.[2] Llavors, aquesta persona opta per la conjectura millor ¿probablement una mera suposició¿, mentre els altres es queden esperant a veure si encerta el resultat esperat. I bastant sovint, quan això no passa, es treuen de sobre l'executiu en qüestió i en van a buscar un altre, i continuen actuant amb la il·lusió que ¿si tinguéssim el ¿líder' adequat, els nostres problemes se solucionarien¿. El que impedeix progressar és la dependència inadequada; per tant, una tasca principal del lideratge és desenvolupar l'assumpció de responsabilitats per part de les persones que formen part del problema.

Quarta, un repte adaptatiu requereix saber distingir el que és valuós i essencial del que és prescindible dintre de la pròpia cultura. En l'adaptació cultural, el treball és triple: aprofitar el millor de la història, deixar enrere el que ja no serveix i, a través de la innovació, aprendre formes de prosperar en el nou entorn.

Per tant, el lideratge adaptatiu és intrínsecament conservador i progressista alhora. El punt d'innovació és conservar el millor de la història mentre la comunitat es desplaça cap al futur. Com passa en biologia, una adaptació reeixida és la que pren el millor del conjunt de competències antigues i descarta l¿ADN que ja no és útil. Per tant, a diferència de moltes concepcions actuals dels processos ¿de transformació¿ cultural, molts dels quals són ahistòrics ¿com si comencéssim totalment de nou¿, el treball adaptatiu, per molt profund que pugui resultar pel que fa al canvi, respecta el passat i la història tant com els qüestiona. Perquè, pel que sembla, ni Déu ni l'evolució fan cap pressupost sobre zero.

El treball adaptatiu genera resistència en les persones perquè tota adaptació requereix que ens desprenguem d¿alguns elements de les nostres formes de treball i de vida anteriors, i això vol dir experimentar una pèrdua ¿una pèrdua de competències, una pèrdua de relacions de reporting, una pèrdua de llocs de treball, una pèrdua de tradicions o una pèrdua de fidelitat a les persones que ens van ensenyar el que nosaltres sabem. Un repte adaptatiu genera una situació que ens obliga a haver de fer concessions difícils. L'origen de la resistència que la gent presenta enfront del canvi no és una resistència al canvi per se; és una resistència a la pèrdua. A tothom li agrada el canvi quan sap que és beneficiós. Ningú no torna un bitllet de la loteria quan guanya. El lideratge s¿ha d'enfrontar, doncs, a les diverses formes de pèrdues reals o temudes que acompanyen el treball adaptatiu.[3]

Basat en la tasca de mobilitzar les persones per tal d¿aconseguir prosperar en contextos nous i desafiadors, el lideratge no consisteix simplement en el canvi, sinó, més profundament, a identificar el que és bo de conservar. És la conservació de les dimensions valuoses del nostre passat el que permet suportar els temors que el canvi comporta.

Cinquena, el treball adaptatiu requereix experimentació. En biologia, l'adaptabilitat d'una espècie depèn dels múltiples experiments que es porten a terme constantment dintre del seu fons genètic, incrementant les possibilitats que en aquesta intel·ligència distribuïda alguns membres diversos de l'espècie trobin el mitjà de prosperar en un nou context. De forma similar, en l'adaptació cultural, una organització o comunitat necessita dur a terme molts experiments, i aprendre ràpidament d'ells, per veure ¿per quins cavalls ha d¿apostar en el futur¿.

La resolució de problemes tècnics de forma adequada i efectiva depèn dels coneixements i de l'acció decisiva d'experts autoritzats. En canvi, tractar els reptes adaptatius requereix habituar-se al fet de no saber on anar o cap on tirar a continuació. En mobilitzar el treball adaptatiu des d'una posició d'autoritat, el lideratge adopta la forma d'elements protectors de la desviació i la creativitat dintre de l'organització malgrat les ineficàcies relacionades amb aquests elements. Si les persones creatives o que parlen clar generen conflictes, que sigui així. El conflicte es converteix en un motor a la innovació, més que una mera font d'ineficàcia perillosa. Gestionar la tensió dinàmica entre creativitat i eficàcia es converteix en una part corrent de la pràctica del lideratge per a la qual no hi ha un punt d'equilibri en què desaparegui aquesta tensió. El lideratge es converteix en improvisació, encara que pugui resultar frustrant no conèixer les respostes.

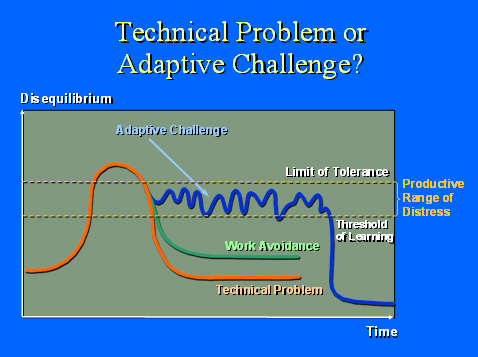

Sisena, l'estructura temporal del treball adaptatiu és marcadament diferent de la del treball tècnic. Es necessita temps perquè la gent aprengui noves formes d'actuar ¿per analitzar detingudament el que és valuós del que és prescindible, i innovar en formes que permetin a les persones projectar cap al futur el que continuen considerant valuós del passat. Moisès es va passar quaranta anys per conduir els israelites fins a la Terra Promesa, no perquè hi hagués un llarg camí des d'Egipte, sinó perquè va caldre molt de temps per canviar la mentalitat de dependència que tenien pel fet d¿haver estat esclaus i generar en ells la capacitat de autogovernar-se, guiada per la fe en quelcom inefable. La figura 2 il·lustra aquesta diferència en l'estructura temporal.[4]

Figura 1: Problema tècnic o repte adapatitiu?

Desequilibri; Repte adaptatiu; Límit de tolerància; Franja de malestar productiva; Llindar de l'aprenentatge; Evitació laboral; Problema tècnic; Temps

Setena, els reptes adaptatius generen evitació. Atès que és molt difícil que una persona pugui resistir llargs períodes de trastorns i d¿incertesa, els éssers humans de forma natural duen a terme una sèrie d'accions per tal de restaurar l'equilibri el més ràpidament possible, encara que això impliqui evitar realitzar el treball adaptatiu eludint fer les tasques difícils. La majoria de les formes del fracàs adaptatiu són conseqüència de la nostra dificultat per contenir períodes prolongats d'experimentació, amb les discussions difícils i conflictives que els acompanyen.

L¿evitació laboral és simplement l'esforç natural per reinstaurar un ordre més familiar, per restablir l'equilibri social, polític o psicològic. Encara que es donen moltes formes diverses d¿evitació laboral segons les cultures i els pobles, sembla que s¿observen dues vies comunes: la dilució de responsabilitat i la desviació de l'atenció. Ambdós camins funcionen molt bé a curt termini per evitar assumir el treball adaptatiu, però deixen les persones més desprotegides i vulnerables a mitjà i a llarg termini. Algunes formes usuals d'eludir responsabilitats són: buscar un cap de turc, culpar l'autoritat per la persistència dels problemes, buscar un enemic extern o matar el missatger. Desviar l'atenció pot adoptar la forma de: solucions enganyoses, com el Vedell d'Or; intents de definir els problemes de manera que encaixin dintre de les pròpies competències; reiterats ajustaments estructurals; l'ús defectuós dels consultors, els comitès i els grups de treball; els conflictes estèrils i les lluites de poder (¿A veure com lluita el colós!¿), o la negació absoluta.

Vuitena i última, considero que el treball adaptatiu és un concepte normatiu. El concepte d'adaptació sorgeix dels esforços científics per entendre l'evolució biològica.[5] Aplicat al canvi de les cultures i les societats, el concepte es converteix en una metàfora útil, però inexacta.[6] Per exemple, les espècies evolucionen, mentre que les cultures aprenen. L'evolució és interpretada, en general, pels científics com una qüestió de canvi, mentre que les societats sovint deliberen i planifiquen conscientment, i experimenten intencionadament. Més a prop del nostre interès normatiu, l'evolució biològica s'ajusta a les lleis de supervivència. Per la seva banda, la societats generen propòsits més enllà de la supervivència. El concepte d'adaptació aplicat a la cultura planteja la pregunta següent: Adaptar-se a què, amb quin propòsit? Què vol dir prosperar? Què volem dir amb progrés, com a empresa o com a comunitat?

En biologia, la funció ¿objectiva¿ del treball adaptatiu és clara: prosperar en nous entorns. La supervivència pròpia i la dels qui duen els mateixos gens defineixen la direcció de l'adaptació dels animals. Una situació es converteix en un repte adaptatiu perquè posa a prova la capacitat d'una espècie de transmetre el seu patrimoni genètic. Així, doncs, quan una espècie és fructífera multiplicant i protegint els seus i assoleix transmetre els seus gens, es diu que ¿prospera¿ en el seu entorn.

Prosperar és més que afrontar una situació. Res no és trivial en biologia amb relació a l'adaptació. Alguns salts adaptatius transformen la capacitat d'una espècie i provoquen un procés creixent i profund de desenvolupaments adaptatius que condueixen a un ventall ampli de formes de viure. Tot amb tot, el fet de prosperar en sistemes biològics és definit per la progènie.

En les societat humanes, ¿prosperar¿ adquireix una sèrie de valors que no es limiten a la supervivència de la pròpia espècie. Els éssers humans són capaços de sacrificar àdhuc la pròpia vida per defensar valors com la llibertat, la justícia i la fe. Així, doncs, el treball adaptatiu en les cultures implica l'aclariment de valors i la valoració de les realitats que qüestionen la realització d'aquells valors.

Com que la majoria de les organitzacions i comunitats respecten una combinació de valors, la competència dins aquesta combinació explica, en gran part, per què el treball adaptatiu suscita amb tan sovint conflictes. Les persones que tenen valors en conflicte discuteixen entre elles quan afronten una situació compartida des dels seus respectius punts de vista. En un cas extrem, i so no existeix cap mètode millor de canvi social, el conflicte sobre els valors pot resultar violent. La Guerra Civil americana va canviar el significat d'unió i llibertat individual. L¿any 1857, assegurar-se la tranquil·litat de la llar significava restituir els esclaus que s'havien escapat als seus propietaris; el 1957, significava utilitzar les tropes federals per tal d¿integrar la Central High School a Little Rock.

Algunes realitats posen en perill no tan sols un conjunt de valors més enllà de la supervivència, sinó l'existència mateixa de la societat, si no són descobertes i afrontades a temps per les funcions d'aclariment de valors i d'examen de la realitat d'aquesta societat. En opinió de molts ecologistes, per exemple, el fet que ens centrem en la producció de riquesa més que en la coexistència amb la naturalesa ens ha fet descurar els factors fràgils del nostre ecosistema. Aquests factors poden ser rellevants per a nosaltres si finalment comencen a posar en perill els nostres valors principals de salut i supervivència, però quan això passi potser ja haurem pagat un preu molt alt pel dany causat, i els costos i les dificultats de l'ajustament adaptatiu poden haver augmentat enormement.[7]

Així, doncs, el treball adaptatiu demana que reflexionem sobre els valors amb els quals busquem prosperar, i exigeix diagnosticar les realitats que amenacin la realització d'aquests valors. Més que legitimar un conjunt adequat de pressupòsits sobre la realitat, més que denegar o evitar les contradiccions internes d¿alguns dels valors que més apreciem, i més que anar fent, la tasca del progrés adaptatiu implica buscar proactivament aclarir les aspiracions o desenvolupar-ne de noves, i suposa també el treball tan dur de la innovació, l'experimentació i el desenvolupament cultural per tal d¿aconseguir aproximar-se més a aquelles aspiracions amb què definiríem el significat de ¿prosperar¿.

En altres paraules, els tests normatius del treball adaptatiu impliquen una valoració tant dels processos pels quals s'aclareixen els valors orientadors en una organització o una comunitat, com la qualitat de l'examen de la realitat pel qual se n'obté un diagnòstic més exacte, i no el més que l'adequat. Mitjançant aquests tests, per exemple, donar solucions falses als nostres problemes col·lectius buscant caps de turc i assenyalant enemics externs, com es va fer de forma extrema a l'Alemanya nazi, podria generar masses de partidaris enganyats que fàcilment concedirien una autoritat extraordinària als xarlatans a curt termini, però no constituiria un treball adaptatiu. Com tampoc són de lideratge les accions polítiques per guanyar influència i autoritat cedint als desitjos dels qui només cerquen respostes fàcils. En efecte, les persones enganyades amb el temps poden produir el fracàs adaptatiu.

Ronald A. Heifetz és professor King Hussein Bin Talal en Lideratge Públic a la John F. Kennedy Shool of Government (KSG), Harvard University. Fundador del Center for Public Leadership de la KSG, Harvard University.

[1] Ronald A. Heifetz, Leadership without Easy Answers (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994), p. 76.

[2] Ronald A. Heifetz, Donald Laurie, ¿The Work of Leadership¿, Harvard Business Review, enero de 1997, reeditado en diciembre de 2001.

[3] Ronald A. Heifetz, Marty Linsky, Leadership on the Line: Staying Alive through the Dangers of Leading (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002), cap. 1.

[4] Ronald A. Heifetz, Donald C. Laurie, ¿Mobilizing Adaptive Work: Beyond Visionary Leadership¿, en Conger, Spreitzer, Lawler (eds.), The Leader¿s Change Handbook: An Essential Guide to Setting Direction and Taking Action (Nueva York: John Wiley & Sons, 1988).

[5] Véase Ernst Mayr, Toward a New Philosophy of Biology: Observations of an Evolutionist (Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1988); Marc W. Kirschner, John G. Gerhart, The Plausibility of Life: Resolving Darwin''s Dilemma (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

[5] See Ernst Mayr, Toward a New Philosophy of Biology: Observations of an Evolutionist (Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1988); Marc W. Kirschner and John G. Gerhart, The Plausibility of Life: Resolving Darwin's Dilemma (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

[6] See Roger D. Masters, The Nature of Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989).

[7] Ronald A. Heifetz, Leadership Without Easy Answers (Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard University Press, 1994), pp. 30-32.

És obligatori estar registrat per comentar.

Fes clic aquí per registrar-te i rebre la nostra newsletter.

Fes clic aquí per accedir.